Mountaineers call the elevation above 26,000 feet, or 8,000 meters the “death zone.”

At this height life becomes unsustainable. The risk of altitude-related illness skyrockets, decision-making is impaired, and it becomes difficult if not impossible to eat or sleep. There is just not enough oxygen in the air.

At the beginning of the 1950s, not a single person had set foot atop one of the world’s 14 8,000-meter peaks and lived to tell the tale. By the end of the decade though—thanks to relaxed rules around international travel in the Himalaya and advances in high-altitude mountaineering equipment—12 of those 14 peaks had been summited.

At 28,251 feet above sea level, K2 is the second-highest mountain on earth and the deadliest of the five tallest peaks in the world. In 1953, it was also the objective of an American expedition led by Charles Houston and outfitted by Eddie Bauer.

DESIGNING FOR THE DEATH ZONE

Organizing a high-altitude mountaineering expedition is like putting together a puzzle—you have to find the pieces that fit together. As Houston assembled his eight-member team, three climbers from Seattle made the cut.

Knowing the kind of conditions they’d be facing, those three climbers approached Eddie Bauer to ask for a mountaineering parka that could withstand the intense cold and unpredictable weather of K2.

Building on the success of the Skyliner Jacket’s innovative down insulation, Eddie set out to design a jacket worthy of the expedition. He named the result the Kara Koram Parka—a variation of Karakoram, the name of the mountain range in which K2 stands—and sent a prototype to Houston for his appraisal.

Houston wrote back, “This is the finest article of cold-weather, high-altitude equipment I have ever seen.”

ATTEMPTING K2

The Houston-led K2 expedition was not only seeking a first ascent, but they were also attempting to do so without the use of supplemental oxygen—something that had never been tried on a mountain of that height.

Houston’s experience as a mountaineer, doctor, and researcher of the effects of oxygen starvation convinced him that, with proper training, climbers could summit the world’s highest peaks without bottled oxygen.

By August 2, 1953, the K2 expedition was well on its way to proving him right. All eight climbers reached Camp VIII at around 25,500 feet, and the plan was to establish Camp IX at a little over 27,000 before attempting a summit push on the 4th. If the weather held.

The weather did not hold. That night, a storm swept in, pinning the team down in their tents on the edge of the death zone.

After five days of howling wind and blinding snow, things got worse. On the morning of August 7, with food and gas supplies dwindling, Art Gilkey, a geologist from Iowa, crawled out of his tent, stood up, and passed out on his way to a neighboring tent.

Once they’d gotten him back inside, Gilkey complained of a pain in his left leg. Upon examination, Houston discovered Gilkey was suffering from altitude-induced blood clots—a potentially life-threatening condition.

Houston gathered the climbers and explained that without supplemental oxygen, the only treatment that could save Gilkey was to get him to lower elevation. They voted unanimously to abandon the summit and devote all their resources to saving their teammate.

They discarded all non-essential gear, wrapped Gilkey in a makeshift litter of a tent and sleeping bag, and started to descend. After an hour and a half in the blizzard, with only 200 feet to show for their efforts, and with the avalanche conditions worsening by the moment, the team was forced to return and re-pitch their tents at Camp VIII.

Over the next two days, the team waited and hoped that the weather would improve. Three of the climbers, Seattleites Pete Schoening, Bob Craig, and Dee Molenaar, used the time to scout a better descent route and retrieve fixed ropes to aid in lowering Gilkey down the mountain.

By the morning of August 10, Gilkey’s blood clots had spread to his other leg, and he was showing signs of pulmonary edema. Houston told the team, “If he has any chance to survive, we’ve got to get off the mountain now—regardless of what the weather is doing.”

THE FINAL PUSH

Again, the team wrapped Gilkey in the tent and sleeping bag, gave him some morphine for the pain and set out for Camp VII—about 1,000 feet below. After fighting through howling wind and small avalanches that threatened to bury them, the team had made good progress and were within a few hundred yards of camp. Their final obstacle, a steep ice slope situated above a cliff face, required them to lower Gilkey’s makeshift litter on ropes.

While Craig made it to camp and began preparing the tent platforms, three others, Houston, Molenaar, and Bob Bates, descended to Gilkey’s litter, attached ropes, and moved to a narrow ledge near camp where they could guide him toward safety. Schoening anchored the belay from above, hooking his ice axe behind a boulder and shouldering the load.

The final two climbers, George Bell and Tony Streather, were roped together, and they started down the slope to join the three below. Streather made it to the rest of the group without incident, but when Bell started his descent, he slipped, slid down the ice face, and yanked Streather down with him.

As the two fell, their rope tangled with the ropes attached to Gilkey, dislodging Houston, Bates, and Molenaar and sending all five men careening toward a sheer drop thousands of feet onto the glacier below. Schoening saw that the tumbling climbers were on track to intersect his belay rope and threw himself onto his ice axe in hopes of arresting their fall.

Moments later, the falling climbers’ ropes tangled on Schoening’s rope and he found himself holding the weight of six other men with only the assistance of his miraculously intact ice axe. The five climbers came to rest, hanging upside-down and badly battered.

Schoening’s incredible save that day became known among American alpinists simply as “The Belay.”

Once they were finally able to climb back up the slope, the team took stock. Houston had a concussion and was disoriented; Molenaar had broken ribs; Bell had lost his glasses and was snow-blind; and Schoening was freezing and exhausted from holding the belay. The team could go no further that day, so they anchored Gilkey in place with two ice axes and told him to hang tight while they went to set up the tents.

When they returned 45-minutes later, Gilkey was gone.

At the time, the team assumed that another avalanche had swept him off the slope, but years later Houston said that he thought Gilkey had purposely worked himself loose, sacrificing himself so the rest of the team could get to safety.

It took the team five more days to get off K2.

A LASTING LEGACY

When Schoening returned to Seattle, he and the other climbers were regarded as heroes for their selfless attempt to save their companion. While the expedition was ostensibly a failure, the team’s courageous rescue attempt and successful descent have earned it a place in the history of high-altitude mountaineering.

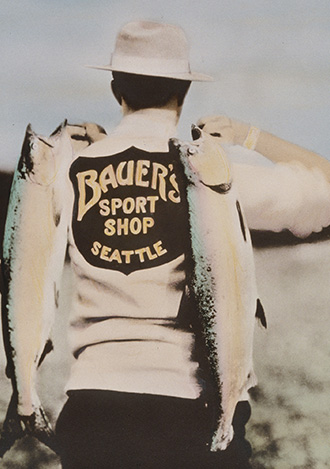

Similarly, the renown of the expedition brought fame to Eddie Bauer and the Kara Koram Parka. The team called it the best mountaineering jacket they’d ever used, and for the next 30 years, Eddie Bauer became known as an “Expedition Outfitter,” supplying equipment to virtually every major American mountaineering effort.

Five years later, Pete Schoening was part of another expedition to the Karakoram to climb Gasherbrum I—26,510 feet tall and the second-highest unclimbed peak in the world at the time. He and his team wanted to use the Kara Koram Parka again, but approached Eddie Bauer in hopes that the warm, heavy parka could be made lighter.

Eddie had been using ripstop nylon in his sleeping bags for a few years and agreed to try it in place of the heavy cotton face fabric used on the original. The new, lighter fabric allowed him to add more down, making for a lighter, warmer parka. On July 5, 1958, Schoening and his partner stood atop Gasherbrum I in their iconic Kara Koram Parkas.

Visit the Eddie Bauer Historical Archive

Learn more about the history of Eddie Bauer and read more stories like the one above.