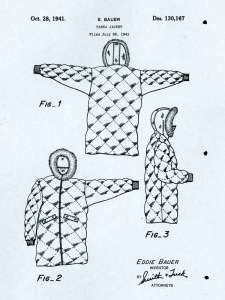

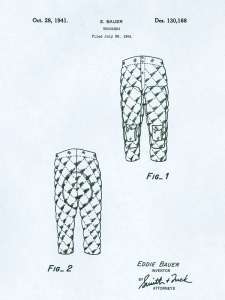

By the time the United States entered World War II in December of 1941, Eddie Bauer had been designing and selling down outerwear for five years. Some of his earliest customers were military personnel. They were particularly interested in a down flight suit that Eddie had developed. Consisting of the Bauer Down Parka and Down Flight Pants, the suit was being used by bush pilots in Alaska and getting rave reviews.

Left: Bauer Down Parka: Illustrations from the 1941 design patent. | Right: Down Flight Pants: Illustrations from 1941 design patent.

During the late 1930s, a pilot stationed at the Sand Point Naval Air Station in Seattle tried the suit and told several of the other Sand Point flyers. They also bought Eddie’s suit and were impressed. Word spread.

Six months after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the Japanese attacked the Aleutian Islands, establishing garrisons on Kiska and Attu. In response, the U.S. Army Air Forces significantly increased their presence in Alaska, at Elmendorf and Ladd Fields. The Aleutian Campaign became a year-long battle to drive the Japanese out of the archipelago. Flyers began ordering Eddie’s flight suit, paying for it out of their own pockets. Far lighter than any of the wool, kapok or shearling insulated suits then available, Eddie’s down option was also warmer than any of the others.

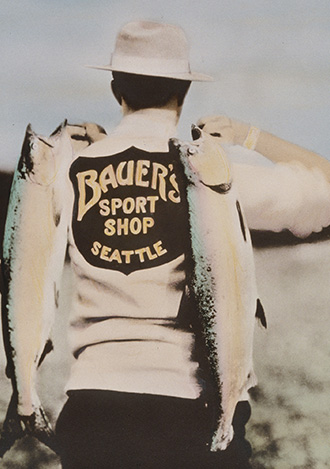

Photo: Bauer Down Parka: The hood ruff and face guard is wolverine fur.

Emergency Relief

Early in 1942, Eddie had gotten a call from the Army Quartermaster’s office. A Japanese submarine had sunk a cargo vessel en route from Seattle to Alaska. The cargo, which included sleeping bags and snowshoes for the troops in Alaska, had been lost with the ship. As an emergency replacement, the Quartermaster Corps assigned Eddie the responsibility of purchasing every available cold weather sleeping bag in North America. He was also instructed to procure replacement snowshoes and snowshoe harnesses.

To accomplish this, he enlisted the help of L.L. Bean, Abercrombie and Fitch, Gokey Co., The Woods Sleeping Bag Co. and every other outdoor equipment supplier he could find. They shipped their gear to Eddie in Seattle, where it was organized and invoiced according to the Quartermaster’s guidelines.

Freezing the Down Supply

Shortly after this, the War Production Board froze all commercial use of feathers and down, along with other materials essential to Eddie’s normal business production, including fabrics, zippers, and snaps. They were all requisitioned for the manufacture of Army sleeping bags.

Eddie’s response was to work with Ducks Unlimited, publicizing to American hunters the need to support the war effort. They were encouraged to harvest all the feathers and down from the geese and ducks they got and send it to Seattle where it was cleaned, sorted, and sent on to the Army. This “Gathering Campaign” secured thousands of pounds of feathers and down and provided Eddie with an unexpected benefit—lots of free advertising.

“It would have been impossible for any small operator to purchase the many, many thousands of dollars of space that was given to advertising this effort. The goodwill that came from this was priceless. It was of great benefit and advertising value for the years to come,” he said.

Faced with the prospect of having his business virtually shut down because of the freeze on materials, Eddie made a simple choice: He went into the production of sleeping bags for the Army.

His first order in 1942 was for 1,000 bags, to be delivered within 60 days. When he made that delivery, he was told that other contractors were so far delinquent on their deliveries that he could manufacture a second thousand. He did so, without a problem.

1942 Sleeping Bag: Production improvements set Bauer bags apart.

Around the same time, the War Production Board ordered 10,000 pack boards, and demanded shipment within two days. Eddie worked with another Seattle sporting goods company, Osborn & Ulland, in assembling these pack boards. They were delivered on time.

Production Secrets

The fact that Eddie was able to produce the sleeping bags faster and more easily than other contractors was no accident. He developed production methods and machinery to streamline the process and save both time and money.

The first improvement he made was in automating the system for marking the bags’ seam lines. Ordinarily, this took two men manually ruling the lines with a straight edge and chalk after the fabrics had been cut for the bag. Eddie’s new system allowed the cutting and ruling to be done in a single pass.

His second improvement was designing a system that allowed one sewing machine operator to assemble all the zippers and webbing required for a sleeping bag. The webbing was fed on rolls to the sewing machine. The zippers were also fed, one after the other. So all the “connecting” materials came out fully assembled, only requiring to be scissor cut for final production.

Finally, Eddie designed a simple piece of equipment for packaging the finished bags more efficiently. Again, standard practice had been to use two men to forcibly roll the bag tightly enough so that it would fit into a container 11.5″ square. With Eddie’s device, one man could roll the bag tightly enough to fit into a container 8.5″ square. It was not only faster, it saved dramatically on storage space during transport.

1943 B-9 Parka: The down-insulated parka was rated to -70°F.

These refinements meant one thing: Eddie was able to underbid all other contractors, and he got a lot of contracts. By the end of 1942, he was running shifts 24 hours a day, and working on an order for 220,000 sleeping bags.

The Cold Weather Buoyancy Flight Suit

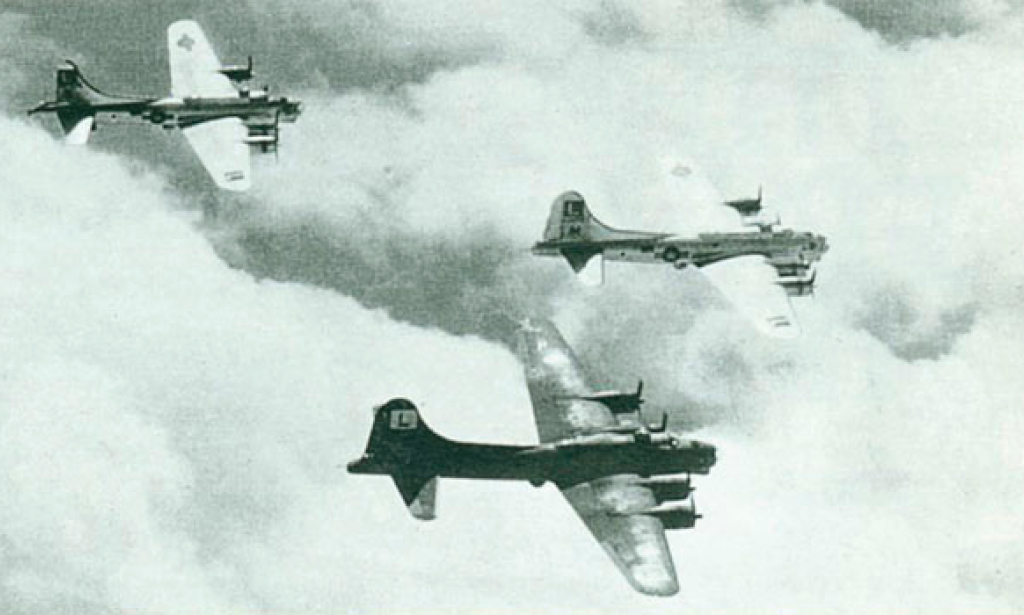

One day, in the middle of that production, Eddie got a call from the U.S. Army Air Forces’ Materiel Lab at Wright Field in Dayton, Ohio.

“Are you the Bauer who’s been supplying down flying suits to the officers stationed up at Elmendorf and Ladd in Alaska?” the officer asked.

“Yes, I’m Eddie Bauer.”

“Well, we’ve got a Boeing bomber that’s leaving Seattle tomorrow morning for delivery here at Wright Field. We want you to be on it.”

Eddie said, “That’s impossible, sir. I’m in the middle of 24-hour-a-day production of high priority sleeping bags for the Army.”

The officer’s response was unequivocal. “We’ll take care of that. We can overrule any priority they have. We need you in Ohio.”

Eddie agreed to come, but said that he preferred not to fly on the bomber. He promised to get on a train and be there in four or five days.

When Eddie arrived at Wright Field, he was given the requirements for the ultralight cold-weather flying suit he was being asked to design. The two main criteria were: 1) It had to keep a man warm while sitting still for up to 3 hours at -70°F; and 2) It had to keep a man and 25 pounds of gear afloat for up to 24 hours.

The USAAF not only wanted a flight suit, they wanted a buoyancy suit, a life preserver. Never one to shrink from an engineering challenge, Eddie set about designing what became the B-9 Parka and A-8 Flight Pants.

1944 A-8 Flight Pants (two sets): Helped keep a man afloat for up to 24 hours.

The military called it, “The Cold Weather Buoyancy Flight Suit.” Approved for use both by the USAAF and by the Lend-Lease nations, Eddie’s down-insulated suit was the only one to meet the requirements and pass the rigid laboratory tests.

Eddie made 50,000 of the units over the next two years. The basic garment design of the cold-weather suit, with its gusseted sleeves and legs, was also used for midweight and warm-weather suits with a variety of fabrics and insulations, made by other contractors.

Eddie wasn’t done at Wright Field. He was also asked to design a special down sleeping bag.

Like the flying suit, it had to be rated to -70°F. In addition, because one of the intended uses for the bag was to transport wounded soldiers, the zippers had to be constructed so that they could completely enclose a person, yet still be opened at any point along the length of the bag. This was to allow medics access to wounds without uncovering the injured soldiers.

Eddie designed a down-insulated bag that met these requirements and made several production samples. However, he did not bid on the full production, passing his designs on to another manufacturer.

Feather Foam

Despite the War Production Board’s freeze on commercial use of feathers and down, there still wasn’t enough to meet the needs of the war effort. Alternative insulations were needed. Eddie’s solution was a material he called Feather Foam.

It was made of chicken feathers that were curled using a special process that gave the feathers the three-dimensional structure needed to create insulating loft.

Photo: 1942 Sleeping Bag Label: Arctic Feather & Down was Eddie’s company for assembling down and Feather Foam products.

The group at the Materiel Lab in Ohio was interested in Eddie’s idea. The lab tested Feather Foam and found it suitable as an insulator for military sleeping bags. Eddie was asked to return to Wright Field to write the specs for producing Feather Foam in large quantities.

Eddie did so, and large purchase orders for the sleeping bags were issued by the Armed Forces. But since Eddie wasn’t planning to produce the bags, he figured his work was done.

It didn’t turn out that way.

Not long after, Eddie got a call from Ohio telling him there was a problem with the Feather Foam specs. The sleeping bag manufacturers were coming back to the Air Forces saying that the specs for cleanliness were “impossible,” and that the volume of production required was equally out of the question.

“You’ve put us in a jam, Eddie,” they said.

Eddie’s response was that if he could have the proper priorities for the construction of equipment, Eddie would guarantee delivery on all the Feather Foam that was required.

Those priorities were given, and Eddie went to work. Forming a new business, Feathers, Inc., he went into debt to purchase a building and to design and build the special equipment needed to clean and process the chicken feathers.

Conveyors were used to move the material through 8″ tubing during the various stages of production. The feathers were first washed and dried and then sucked into a “Bauer attrition mill” where the curling was accomplished. Finally, the feathers were sent through a 30-foot stainless steel machine that Eddie described as being “something like what’s used in an old-fashioned sausage or meat grinder.”

1942 Feather Foam Sleeping Bag: In military-issue canvas bedroll.

As the feathers were tumbled through the length of this shaft, suction drew off any dust and impurities remaining after the washing process. What emerged at the other end was finished Feather Foam.

Chicken feathers began arriving at Eddie’s plant in train carload lots, each carload containing approximately 14,000 pounds of feathers. At the peak of production, two men were processing one carload of feathers every day.

A National Brand

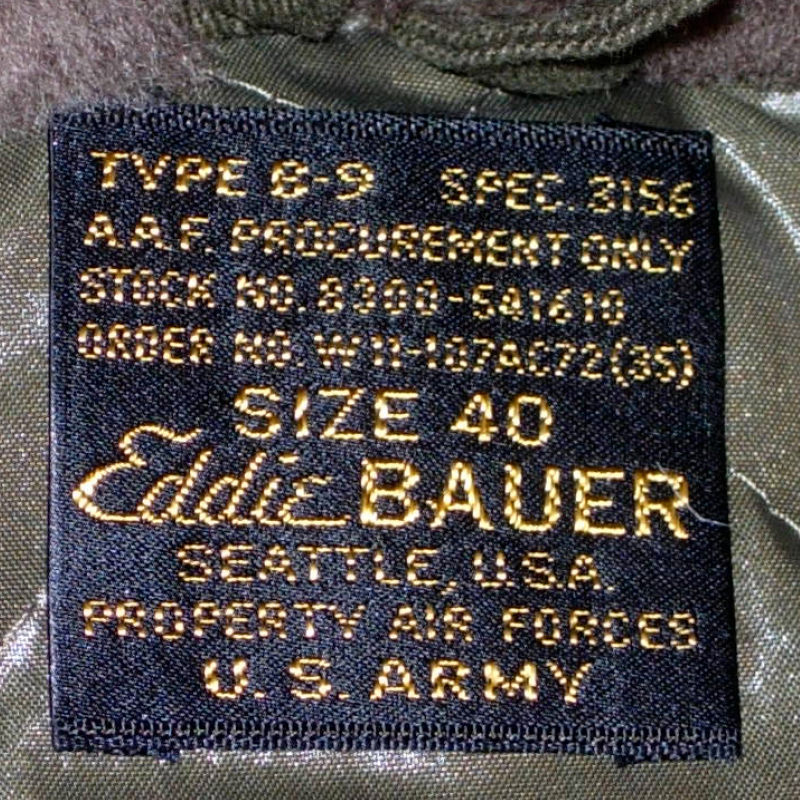

When Eddie developed the B-9 Parka and A-8 Flight Pants for the USAAF, he negotiated the right to have his name included on the military garment label. In addition to it saying, “Property Air Forces U.S. Army,” it also read, “Eddie Bauer Seattle, U.S.A.”

It seemed like a minor thing, considering that the B-9 and A-8 were designed strictly for military applications and never became part of Eddie’s commercial assortment. But at the end of the war, as flyers began returning home, they started writing to “Eddie Bauer, Seattle, U.S.A.” They wanted to know how they could get more of that down gear.

1943 B-9 Parka Label: Eddie’s name appeared on the military label.

Suddenly provided with a national mailing list, Eddie published his first mail-order catalog. He didn’t have to rely on cold-call marketing either. He sent the catalog, Eddie Bauer Alaska Outfitter, to the servicemen. They already knew his products. They had worn his suit or slept in his bags all through the war and were convinced. “You saved my life!” a lot of their letters said. The catalog business grew quickly.

What had largely been a local and regional operation became a national brand.

Visit the Eddie Bauer Historical Archive

Learn more about the history of Eddie Bauer and read more stories like the one above.